Mycroft Holmes shook the London paper open wide and scanned its contents for any relevant cases he would deal with when he returned to the Assizes court. He squinted in the dim light of the train, forcing his eyes to decode the tiny print, the effort already giving him a headache. A gruff sigh across from him made him lower the opened paper, the top of his head now visible to Inspector Gregory Lestrade, who sat across from him, smoking a pipe. The thick scent of tobacco wafted over Mycroft, triggering his sensitive lungs into a small spasm of protest. He used the open paper to fan the smoke out the open upper window, which was allowing in far too much cold air and misty snow.

"Honestly, Gregory, is too much to ask that you smoke that thing in a more ventilated space? You're courting my asthma."

He stubbornly continued puffing on the pipe, smoke escaping out of a droop on the left side of his mouth. "Would you prefer it was opium?"

"I would prefer if you would toss the fool thing out. You aren't even smoking it properly."

It was a beautiful pipe, carved out of ivory and cherry oak, the subtle engravings of leaves on its rounded bottom a hint of the expert craftsmanship that designed and created it. It was a birthday gift from one of Lestrade's under officers, Inspector Hopkins, whom Mycroft hated with every fibre of his being. Not for rational reasons, for the man was a capable inspector and had steadily risen through the ranks over the years until he now specialized in dealing with homicides alongside Lestrade. But he was a dandy, overly materialistic and fashion conscious, handsome younger man tainted with an eager ambition that wasn't afraid to dip into flirtation. Mycroft was told that Hopkins had no leanings and as he hadn't seen him among certain men, he could assume this truth, though he hadn't seen him among women, either, and as far as he knew the man had no romantic entanglements at all, which was all the stranger.

This didn't stop him from hating on that pipe. Lestrade didn't even smoke tobacco, and Mycroft watched, triumphant, as Lestrade choked and coughed on a deep inhale.

"I assure you I am perfectly capable of smoking a pipe, thought I daresay it is a messy business and perhaps better left to the Scots who are more expert at drawing the flavours of the tobacco in. I think I am doing naught but smouldering. Bugger it, I'll put it out."

His trademark grouchy growl was getting on Mycroft's nerves. They had travelled to the ends of the earth, quite literally, and had visited Gregory's beloved Japan, a place of silk and alien culture and marvellous welcoming people, especially when Gregory revealed he was fluent in the language. Mycroft's cheeks hurt from so much polite smiling and his back had a crick in it from all the bowing.

He had done his research and was lucky enough to get a copy of Yokishaburo Okakura's tome 'Life And Thought of Japan', which gave him an overview of the general mindset of the population he was set to visit. He enjoyed its quiet dignity and adherence to cleanliness of mind and spirit reflected in one's environment. It was strange to think on Lestrade's cluttered stacks of newspapers and not view it as a sort of ailment, for certainly his life in Japan would deem it so. Orderliness was truly a gift of the Buddha. Perhaps Lestrade's messy piles were more a symbol of keeping that which is useful, as they revered knowledge more than money in Japanese society.

Perhaps he was just untidy and there was no changing that, not even via an intervention by a foreign god's influence, nay insistence, that he was courting corruption.

There were many aspects of their excursion that he enjoyed and implemented into his daily life. Mycroft was especially taken with the tea ceremony, a long, drawn-out process where one sat cross-legged on the floor and sipped tea from tiny cups, saying nothing and simply enjoying the tea and the moment as a meditative practise. He felt much calmer afterwards, though he experienced a heightened anxiety over all the clues he'd gleaned about Gregory's adolescent life in that country. The geishas they performed the ceremony with were too understanding of their coded friendship and giggled at a lot of what Gregory said, their bodies lax and easy around him in the way most women of the street were when confronted by men such as themselves. Men who were, in no way, shape or form, a threat to them.

But social mores and international influence were moldable things, and though nanshuko was common with the samurai, it had fallen out of social favour since the advent of sexology. The theories within it upset Mycroft greatly, especially considering the 'special moments' he and Gregory shared, but it was clear the same levels of prejudice were not as strictly enforced and there was no fear of being jailed for something as simple as a rumour. Harmless proclivities were simply accepted. One geisha they had stayed with had one too many cups of sake and began regaling them about how most of her clients would only have sex with her feet and for the last six years of her career, she hadn't needed to have sex at all.

This all makes the experience he'd had in Japan sound sordid, which it most decidedly was not. Gregory had taken him through the more genteel portions of Kyoto and as the sakura blossoms were in full bloom a walk through the city felt magical, with fragrant petals falling on their shoulders as they walked side by side over the small river bridges, schools of koi nipping at the surface of the water and trailing long, beautiful orange fins in the gentle current.

He could understand how Gregory had fallen in love with Japan, but for Mycroft it was a pleasant excursion and nothing more. He longed for the dreary aspect of home.

And he was still in the dark. What he'd really wanted was to learn Gregory's secrets and where his samurai sword had come from, and to hear wild tales of his youth. But all of his friends in Japan were strangely tight lipped about his past and his time with the last remnants of the Shinsengumi, elderly men who taught him martial arts and a sense of profound discipline. Their abolishment in the 1871 uprising was still a sore spot for many, but it was surprising to Mycroft that Gregory had not been in direct training of a samurai but was, oddly predictably, trained by a former Edo samurai who became a police officer in 1870. He was a significantly older man and Mycroft did not glean any manner of romantic attachment, though mention of 'Toshi' was brought up by him several times, and each mention of that name made Gregory's grin falter, and his skin take on an ashen hue. You couldn't find enough sake to fill him up in those moments.

Japan had been like an alien world, and while Mycroft enjoyed the strangeness and the beauty of it, he was also an English gentleman, and as such longed for his stinking Thames and the misty, dreary shores of his beloved London. Japanese food was clean and fresh, but he often longed for a dodgy pork pie and thick gravy, the kitchen doused in rosemary and sage as Mrs. Hudson cooked them a healthy dinner. He missed their room and the easy company and banter. He even longed for Dr. Watson's routine visits and the long-winded conversations he would entertain them with. He missed the shouts of haberdashers and street vendors, and his ability to leave all of it behind the door of the Diogenes Club, with its musty old law men and carefully catalogued books of legal reference, a roaring fire the only sound in the place.

He missed Donald's excellent cakes, from his cafe attached to the Diogenes, for while Japan had incredible and delicious fish and rice dishes, they were not enamoured with sugar and cream and all the magic that such a combination could create. He'd lost weight, while Gregory somehow remained as robust as ever, a healthy glow to his skin and his muscles even more defined. His visit with his police inspector friend Saitou had resulted in some training exercises he was keen to incorporate into his daily fitness routine. Mycroft was more inclined to practise a mirroring exercise called Tai Chi that Saitou's Chinese maid incorporated into her morning routine, and she encouraged him to practise with her, each movement slow and graceful and giving a calming sense of one's body movements and an awareness of its connection to mind and muscle.

Still, for Lestrade to take on a punishing exercise regimen seemed silly, for they were both no longer young men, and over the years too much had changed since Lestrade had joined the Yard and his work had become less physical and more desk bound. Chasing suspects was up to the lower level officers, and Gregory found himself more and more at the mercy of papers, his time spent going over photographs of crime scenes and having both gentle and harsh conversations with witnesses. Fingerprinting was well established as a method of identification and it was quite surprising how imperfect human memory truly was, as evidenced by the guilty perpetrators Lestrade arrested. Some were claimed thanks to what they were wearing or a specific physical trait, but the overall descriptions were often murky or, worse still, contradictory. The fingerprints were the ideal map of a person's identity, and Lestrade studied his catalogue like a religious zealot.

The police in Japan still relied on torture and confessions, an imperfect method that Lestrade openly criticized. He had a few heated conversations with Inspector Saitou that nearly ended in violence, but every time both of them would size each other up, they would see an equal opponent who just wanted the same thing—Justice—and they would both back down, have another cup of saki and again be fast friends regaling each other with tales of crazy arrests and cross dressing geishas.

They had, of course, bought several camphor trunks carved with ornate lotus leaves and sakura trees to hold the plethora of goods to bring home. Mycroft joked that they had brought half of Japan back with them, to which Lestrade tersely replied that they might as well as it was unlikely he would ever step on her shores again. Lestrade looked upon the shrinking Tokyo horizon with a sense of longing while Mycroft faced the other direction, eager to be back in London.

The boat ride home was long and arduous and lacking all the fun anticipatory excitement the adventure to Japan afforded. Lestrade, humming a tune as he smoked from his pipe like an inexpert opium user, was clearly rejuvenated from the long trip. The sea air whipped across his strong features as though it further fortified his strength of purpose. Mycroft spent most of his time in the cabin, fighting the usual effects of the damp with eucalyptus and mint infusions, his lungs irritated by the salty air. The only joy he felt on that return trip was the pleasure of being back in England, and the promise of a soft bed that was a good foot off of the floor. His back still ached from the prolonged time spent on a tatami mat and its hard futon mattress.

Lestrade slept like a baby and had nary an ache upon waking. In fact, he was pleased with how the floor arrangement had cured a few of the knots in his back. Though he'd begged they try it, Mycroft refused to adopt the practise at 221B.

They were now on the final stretch of their journey home, the train rocking them gently into a sense of coddling comfort, the smell of leather, sweat and tobacco thick in the air between them.

"Mrs. Hudson will not be waiting for us," Mycroft informed him. "She is busy with her final flying lesson and will not be back in London until Thursday afternoon."

He folded his paper neatly and placed it on the chair beside him, a photography of an aeroplane beneath the headline.

Lestrade still puffed inexpertly on his pipe. "Has she decided?"

"Really, Gregory, there's no way a woman of her age would get the medical clearance to do such a thing. It's not a matter of how she 'feels' it's about practicality."

"I understand, but our Mrs. Hudson is a stubborn sort of woman."

"There is stubborn and then there is foolish. She is not the latter. No, from what I gleaned from her last letter, she has resolved to assist the attempt to ensure the pilot has the best health possible before he undertakes his journey. He intends to make history with his world-wide flight, one that should prove quite daring going over the vast expanse of the Atlantic."

"Imagine taking to the skies to go to Japan, Mycroft," Lestrade said, a gleam in his eye. "We could leave in the morning and be there for a simple tea ceremony by late afternoon. I do rather like the open air of the sea, however. It reminds me of my youth."

"How fortunate for you. It only reminds me of the chamber pot."

"Those rogue waves made you turn a lovely shade of green. I was thinking we could paint the parlour that colour."

"You are an absolute cad."

"There's nothing wrong with a bit of redecorating."

Mycroft waved away a plume of smoke from Lestrade's pipe as Lestrade choked on the smoke, thickly coughing. "Put that fool thing out. You're a terrible smoker."

Lestrade looked at the pipe with a sense of sad longing and obliged, tapping it out on the ashtray beside him. "I think I'd prefer Saitou's thin cigarettes, but I'm finding this whole smoking business tiresome. My lungs don't feel any healthier, as the claims suggest they should. Bugger it. It makes my clothes stink of smoke anyway, and it stains my fingers yellow. Can't properly taste food, neither, since I started it up." He opened the car window and tossed the pipe into the billowing snow filled night. "That's one souvenir that won't be joining us."

"I don't know why you bothered with it in the first place when you know I can't abide tobacco. My lungs protest it. You seemed overly keen to emulate your friend, Inspector Saitou, and you followed his every habit like an errant puppy."

This was true. Lestrade's friendship with Saitou had clearly gone way back and where Lestrade was muscular and stocky, handsome in that thick way that outdoorsy Englishmen are, Saitou was long and lean, with small, piercing eyes and sharp cheekbones that gave him a starving wolf's appearance. He was quickwitted and handsome, his English perfect, though when he and Gregory slipped back into Japanese banter Mycroft couldn't help but feel left out, that there were in jokes and asides that were too personal between the two of them for him to properly overhear.

He wondered if Saitou was once his lover.

The answer to that question remained mysterious and when they headed back to the docks to get their ship that would take them on the long journey back to America and then rail to New York and then another ship to London, Saitou was conspicuously absent. He did, however, send them off with a gift, delivered to them by a young man who wordlessly handed them a silk-covered box before disappearing within the crowd of travellers.

Lestrade laughed when he opened the black lacquer box that was wrapped in silk. "Rice!" he said, grinning. "Do you think Mrs. Hudson will let me teach her how to cook it? Never mind. We can have it as a reminder meal when we get home and long for the sakura petals of Kyoto."

Again...Not Mycroft's longing.

There was a knock on the door of their passenger booth and Lestrade fumbled looking for tickets. It was not the steward who walked in, but Mr. PInter's nephew Harvey and Willhelm, both of whom had met them in Liverpool to help them load up their luggage into the train. They were no longer the young lads barely out of adolescence who had barely left the village near Holmes Manor, but now had the weathered look of robust entrepreneurs, the streets of London sick with this new breed of energetic and enterprising young men. They had traded their passion for autocars for the new field of aviation, and took to the skies these days more than the roads.

They had recently spent some time at 221B, Baker Street with Mrs. Hudson, who was currently going over the health of an aviator keen on doing a world-wide flight, a foolish and dangerous undertaking that put Mycroft's sensibilities on edge. Surely humankind could understand that mere human beings weren't meant to course the skies, that if they were they would have sprouted feathers long ago? But Mrs. Hudson was as enamoured with the concept as these young men were and had already taken to the air herself a few times under the guise of of seeing how such altitudes affected the human body. If Mrs. Hudson could be fearless before, she was pathological in it now, and even claimed that one is safer in an aeroplane than in an automobile because at the very least, the person running it is an expert whereas every moron has decided they can operate an automobile.

"We were able to get all the luggage off of the boat easily enough, even that big blue metal chest. It's a good thing you opted for us to come to London to help you transport it. Bloody busy, it was."

"It was quite a feat for you to come direct to London from Japan. It seems a miracle to me, even with the Suez open." Willhelm leaned against the doorframe, his slender hip propped on the lock. "I would like to go to Japan one day. Their steamships are formidable. Is it true they eat on the floor?"

"Tatami mats," Lestrade answered, bemused. "And not on the floor. They use small lacquered tables and one sits on one's ankles, which strengthens the posture."

Willhelm was not convinced. "That seems unnecessarily uncomfortable."

"Only if you have rheumatism, I should think," Lestrade replied. He waved his unlit pipe at Harvey, Mr. Pinter's nephew. "I heard a rumour from Mrs. Hudson that you are now married. Is that true?"

Harvey blushed. "Yes, Sir. A fine young girl, you may know her. She worked under Mrs. Healey for some time before getting her secretary certificate."

"Betsy," Mycroft and Lestrade said in unison.

"She's a lovely, smart girl," Mycroft offered. "Has she fully abandoned Mrs. Healey in favour of London?"

"It was an easy move," Harvey admitted. "All her family is in the village and she enjoyed her employ at Holmes Manor, especially after Miss Oakes and Miss Turner moved in, but it's a big job taking care of that place and Betsy was of a mind to get her stenographer training and is doing secretarial work for the phone company now. It's a good job, and she likes it immensely. As for me, well, the sky is not my limit, is it? It's what I'm primarily focused on. You should see the magic of it sometime, the way the engines are put together and the expanse of the wings. Do you know, they don't really understand the exact science how of how it all works, it just does. It's like cheating physics, it was explained to me. I'm not a math man, but I love that take off and the rush when you get in the air."

"A far cry from your uncle's horse and carriage," Mycroft observed.

"I'd say! And the best part is travelling light!"

He bit his tongue after this, recognizing his slight faux pas, considering Lestrade and Mycroft had brought half of a country with them in luggage and the aforementioned horse and carriage were to be the main transport for the bulk of it. Smaller items were going into the trunk of the autocar Lestrade had finally purchased earlier that year, and Mycroft still could not drive it, citing his fainting habit, which was unfair since he hadn't had a turn in years. There was still a clutch of reckless youth attached to Harvey that Mycroft found amusing and it was clear his head was well into the clouds instead of in this stodgy train car full of the stink of Lestrade's now abandoned tobacco.

"Well, congratulations to you and Betsy and your flights in the future. Willhelm, will you be accompanying them in kind? Has any young lady caught your eye yet?"

Willhelm, freckle faced with red curly hair and a thick German accent, usually exceptionally chatty, faltered over his perfect grin and ran a nervous hand through his tangled curly locks. "Not yet, no. I've been very busy."

Mycroft bit back on his smile and tried to keep his smirk hidden. He'd long had suspicions of Willhelm's preferences, but he kept them stubbornly to himself. The young man was familiar enough with Mycroft and Lestrade to understand the 'friendship' they possessed and if he was willing to open up to them about his preferences, only then would they elicit advice. It was not an easy thing to be what people called an invert, an ugly label that held great prejudices and danger within it in English society and other pockets of the world.

The train ground to a halt and Willhelm saw his chance to escape from the conversation. "We are now at Piccadilly," he said, too eager to get away. "The carriage will wait, we will unload it, and Harvey will be back for you to drive you to 221B by auto."

"Is Dr. Watson joining us?" Lestrade cheerfully asked.

Mycroft felt an inward dread, for though he loved Dr. Watson dearly, as did Lestrade, the man's long-winded discussions and analysis of their trip would test the very boundaries of his patience. Yes, it had been several months since they had seen him, but Mycroft longed for the familiar solitude of his rooms and a warm fireplace surrounded by quiet, familiar things and a comfortable chair before it where he could enjoy the warmth from the comfort of worn oak instead of on his ankles on a hard floor.

Posture be damned, his back was killing him!

Though it was a late hour, Piccadilly Station was a mob of travellers, most of the throng domestic within London and the surrounding towns. As a beginning port of travel, its passengers grew in number every year until there were times one could barely get into the train car without hitting a dozen shoulders, one's shins knocked hard from the amount of metal cornered luggage traipsing through the queue. He wondered how riots didn't regularly erupt, and chalked it down to simple English sensibility, where one didn't grumble and manners trumped all other competing emotions.

The snow was thicker now, and it fell on their shoulders, dusting them like icing. Dirty clumps of it lay muddy and thick against the rails, the platform grimy and staining the wool hems of women's dresses as they hurried towards the train. Crying children and singing grandmothers crowded the lower class cars, their battered suitcases following them. Japan had been just as distinctive between its classes, perhaps even more so with everyone's strictly assigned societal roles and the stringent rules they had to play within them. In this, London was no different.

The contrast was in the noise and anger that ran like a vein through the lower classes of London, a sense they were little more than rats on a dock and, well, they knew it. There was a fierce pride taken in ignorance that was difficult to translate to their friends in Japan. Saitou's criminal elements were more organized and usually influenced by family rivalries or illegal business practises. The rough edges weren't just more evident here in London, the lower classes celebrated them.

Murder was a rarity in Japan, but when it happened, it was much like the way of all evil—undiscriminatory. In London, it was mostly rooted in poverty and socially ill. Not quite an every day occurrence, but common enough among ruffians that violent death rarely earned an article in the London Gazette.

He shook his head. Why think of murder when they were at last home, and the warmth of a fire beckoned to him from the damp and the cold? He shivered and Lestrade lent him his jacket, which he pulled tight around his slight frame.

It felt like it took forever for them to leave the stopped train as they journeyed down the corridor to the small door leading to the platform. They stood beneath a gaslight and waited for Harvey to arrive with the autocar to take them the rest of the journey. Willhelm was already in the luggage carriage, waiting for the remaining suitcases to be unloaded. There seemed to be many passengers with excess baggage on this train and both he and Lestrade shivered in the damp chill of a December night, the snow collecting thickly on the ground in powdery, glittering ice.

"It's funny," Lestrade said, looking at Mycroft in a soft, thoughtful way that Mycroft found both embarrassing and endearing. "In this light, the way the shadows form on your cheeks..." A distinctive glimmer arose in Lestrade's eye, one that Mycroft knew well. "You look Japanese. Incredibly so. I think our trip has rubbed off on you."

"I think you are tired and I my longing for tea and biscuits belies my true English nature."

"I think you've tested your English nature. You got along like chips and vinegar with the geishas."

"I am not a man of many prejudices." Mycroft closed his eyes as he leaned heavily on his cane. "Though I am thoroughly looking forward to our bed and, at last, a proper night's sleep."

"I can't argue with you there. The ship's cabin we had was rather cramped, and the bed was too small for my frame. My feet kept hitting the wall."

"I'm sure the mattress had fleas," Mycroft complained.

"No point whinging about it now. We're on our familiar soil, after all." Lestrade stamped his foot, chasing the cold from it. "Blast it, Willhielm, Harvey, where are you?"

They stood waiting in front of the station for what felt like hours, at least to Mycroft, his eagerness to be home reaching a fever pitch he'd never felt before, not even after their summer-long excursions to Holmes Manor and the relief he felt to be back in the poisoned air of London. He half wondered if Watson had given the young man his autobus, which he still used to transport patients around the city, a charity offered to house all of their ridiculous luggage. But horse and buggy were now ready to deliver all the camphor chests and additional baggage, and what drove up to meet them was the new model that made a not insignificant amount of passengers turn their heads and stare at the spacious and elegant transport fit for a Lord.

Willhelm grinned at the attention. "I love how this autocar turns heads. They are all looking at us. It is like we are famous."

"I would prefer we weren't," Mycroft complained. "While half of them recognize the auto, the other half recognize myself and Gregory. Dr. Watson's continued success in his novels has made us a household name. It's rather annoying."

"It's also useful," Lestrade said, happily bounding toward the autocar. "We get prime parking and no one complains about us being here, where other carriages and cars aren't permitted. Thank you, good sir!" He tipped his bowler hat to young constable who recognized his superior and refrained from telling him to move the autocar along.

Mycroft felt uneasy at taking advantage of their notoriety, but at present, all he could truly care about was getting home. Willhelm popped the trunk of the autocar and began hauling their suitcases into it with a speed that impressed him. He arranged the various packages and bags in such a way that all of them fit perfectly into the dark space, with room for an additional piece of luggage should it be needed. It was quite a feat of physics.

"If you don't mind my rushing you, sir, we really need to be getting to Baker Street as the carriage will arrive just after us with the remaining luggage and Harvey and I will need to unload that as well. These London carriage drivers are very cranky and don't like to wait long. Please, if you will get in the back seat."

Lestrade obliged and both he and Mycroft got into the red leather back seat, the roof of the car a matching thick leather that was meant to keep them dry from the elements. It did a poor job of it, as snow billowed in through the half side windows that were frozen in place and Willhelm himself was boxed in the front in a full length wool coat, hat and thick mittens as he gripped the steering wheel. He grinned widely, his passion for the vehicle still firmly in place as he turned the engine and brought it roaring to life. Harvey slammed the trunk closed and bounded into the front seat passenger seat beside him.

While it was beneficial that they had an expert driver on their hands, the facts were both Harvey and Willhelm were experienced race car drivers and as such, every journey taken was one fraught with adrenaline fuelled speed and reckless abandon. Willhelm zoomed through the cobblestone London streets as though he was on the track, every sharp turn making Mycroft slip in his seat to careen hard against Lestrade who, by the way, was having a roaring time and laughing over every near miss of hitting a terrified Londoner.

"It runs smooth, ja?"

"Seems to slip a bit on the snow," Mycroft observed as they swerved around a corner. "I say, should you be driving it so fast?"

The car fishtailed as it righted itself. "It is a more difficult auto to manage on ice, and much slower than I am used to," Willhelm complained.

Despite his joy over Willhelm's death defying driving, Lestrade made a face. "Something smells off back here. Mycroft, can you smell that?"

He certainly could. It was a foul, sour scent that reminded him of a butcher's back door garbage.

"Maybe it's just London," he said and Lestrade conceded this was probably true.

But this was wishful thinking as the stench was worse at every sharp turn and Willhelm managed to find all of them. It coated the inside of the car with a foulness that made even Lestrade's strong stomach turn and he held his fist to his mouth, holding in his gag. Mycroft pressed the black wool sleeve of his coat over his mouth and nose, unable to abide it. By the time they reached Baker Street, they were scrambling out of the back seat of the car while the wheels were still spinning. Both Harvey and Willhelm noticed their exit, and each gave them a frowning once ove. Willhelm turned off the engine after parking the car in front of their home and it was then that the smell hit as well, with Harvey leaping out of the car as though it were a thing possessed.

The carriage driver had arrived earlier thanks to some savvy shortcuts throughout the city. His black horse whinnied in distress and took a few steps back from the car, shoving the heavy carriage over the curb and into the lamppost.

Willhelm cursed in German. "What is wrong with her?"

"I don't know," the driver replied. "She was fine the whole trip down and she was well fed and rested before getting back to work here in London town. She's a strong one, this beast, and can well work faster than that contraption of yours. She's used to the noise and bustle and your engine don't bother her none. No, something spooked her proper. In faith, I think I knows, I can smell it from here!"

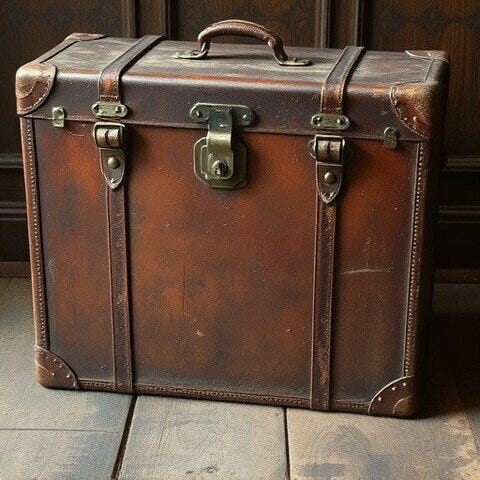

"I've got a mind I know what it is," Lestrade grimly stated. He marched to the trunk of the car and pulled it open, digging out the errant luggage within it and tossing it haphazardly onto the curb in front of their door that proudly proclaimed 221B. "Certainly, Willhelm, you suffered distraction in your duties. We brought a lot back with us, it is true, but we are not men given to unreasonable excess. Bloody hell, that's foul!" He waved his gloved hand in front of his face and pulled his scarf over his nose and mouth before digging out the errant suitcase, then tossing it onto the sidewalk at their front door.

"That's no our suitcase," Mycroft observed. He frowned and pointed at the tag on it with the tip of his cane. "That's not a real rail tag. It looks like a crude forgery." He inspected it closer, though the smell made him instantly reel back. "It's hand painted, with poor skill. What the devil is this?"

Lestrade regarded the suitcase carefully. A wet substance leaked from the bottom. Mycroft moved to open it, and Lestrade stopped him with an outstretched arm.

"Willhelm, how did you get this?"

"It was the last one behind your other boxes, sir. I should have looked more carefully at the tag but it was tucked very firmly in with all of your suitcases and the tag states 22LD, but in the rush I must have thought it said 221B. I simply assumed it was yours."

"It is ours, but not in the way the person who put it there intended," Lestrade gravely replied. "Willhelm, please take the autocar to St. Bart's and get Dr. Zieglar right away. It's only midnight. He'll be in the morgue. I'll phone the Yard from inside." He gave Mycroft a heavy sigh. "It seems we certainly are bloody well home, and it already has made work for us."

"What do you mean? What is all this urgency?" Then, thinking on Lestrade's instructions to Willhelm, "Why do we need Dr. Zieglar?"

To make matters worse, the unexpected appearance of Mrs. Hudson opened the front door, angry hand on hip. "So the two of you are going to just stand on the front step instead of coming in for a hot dinner. Some homecoming!" She sniffed and made a face as she looked down at the leaking luggage near her front step. "What nonsense have you packed in there?"

"Evil and not by our hand," Lestrade informed her.

Mycroft shivered and not from the cold. "Oh, Gregory, it can't be..."

"It most certainly is, Mycroft. There's a body in that suitcase. Back it goes into the trunk and away we go to St. Bart's. Mrs. Hudson, it is lovely to see you and I truly wish we could join you for your welcoming, but it will be hours before we can return. A hot meal sounds like heaven. Is there any way it can wait for us when we get back here in the morning?"

"Stuff and bother, make yourselves bloody sandwiches, then!"

She slammed the door shut.

Mycroft stared at the black lacquered door with a sense of profound longing. Behind it was his bed, his comfort, his life.

"Are you coming, Mycroft?"

Gregory had the car door open, waiting for him.

"Of course," Mycroft assured him, cane tucked under his arm as he slid in the back seat of the auto car behind him, knees bent and wheels forever under them as they were on the road and travelling yet again. He should have known better. Murder and London went hand in hand.

"It's good to be home," Lestrade said, rubbing his hands together.

Mired in bitterness, Mycroft followed him. "Indeed."

________________________________________________________________________

NOTE: This is a WIP of the latest Judge Mycroft Holmes book, written by me, M. Jones. The two previous books in the series are finished and available on my Ko-Fi ( http://ko-fi.com/writermjones )and via Smashwords, Barnes & Noble, etc. I do NOT sell any of my works on Amazon. DM me if you would like a review copy.